roland barfs film diary week 7

diamonds of the night, to die for, big hero 6, control, tange sazen and the pot worth a million ryo

February 15. Wednesday. Yesterday I had a piece published at Vittles, a short essay that has been turned into a short film, about the spaghetti breakfast scene in A Woman Under the Influence. I get the early train to Huddersfield, where I spend the day in a series of conversations, gradually inching closer to understanding what exactly my new job is. I consider staying late after work to go to see some experimental music but realise that I’d rather be at home. The train back to Sheffield is filled with men going to the football. When I get home I cook and eat some lentils, and then watch Diamonds of the Night (dir. Jan Němec, 1964). How should one unwind from another week working at a Holocaust museum? By watching a Czech New Wave film about two teenagers escaping from a train taking them to a concentration camp, of course! I haven’t seen any of Jan Němec’s other work, and in fact hadn’t heard of him at all until fairly recently, but Diamonds of the Night is really a very powerful and intense film which deserves to be better known. Maybe it is in fact already ‘better known’, and everyone who studied film in any formal capacity already knows about it, but I’m pretty sure I’ve only seen one person referring to it in prose, and that’s Peter Cowie in his book where he refers to basically every remotely interesting film made in the 1960s. More than anything, Diamonds of the Night reminds me of Son of Saul, that particularly intense and horrible film about the death camps and the compromised and futile position that inmates were forced into — Němec’s film has, at points, especially in the long opening tracking shot, a similar kind of psychological intensity as László Nemes’ film, achieved by too-close close-ups on the characters, the camera loitering uncomfortably near the protagonists’ skulls, creating a kind of voyeuristic pressure that isn’t quite empathetic and doesn’t quite encourage identification while, at the same time, making sure the spectator can’t look away. Němec doesn’t sustain this approach or style to the same degree that Nemes does, but that’s because he’s doing something different to Nemes anyway. The missing link between these two directors is probably Béla Tarr, really, whose work extends the opening shot of Diamonds of the Night to monstrous, gargantuan, miserable lengths. After this incredible opening shot of the two protagonists jumping off the train and fleeting through a deep and hostile forest (apparently at that point the most expensive shot in Czech cinematic history), Diamonds of the Night then becomes a film about dream and fantasy, aggression and fear, a kind of murky and subterranean drifting through a forbidding landscape, in which the protagonists are constantly at risk of capture or punishment or violence, and in which they both experience violent, revengeful, erotic fantasies. After escaping from the transport, they become trapped in a desolate, stripped back world, where human interaction is reduced to threatening transactions. There is something of Kafka about this, of course, but more Kafka’s woozy, uncertain depiction of reality, where the world can shift unsteadily under your feet, than his depiction of the bureaucratic machine devouring individuals (though that’s in the background too). One of the protagonists has visions of everyday life in a city; scenes in which he’s always wearing a coat with the letters KL on the back (Konzentrationslager), marking him out as an exile who can’t be reconciled with the world: it doesn’t matter whether these scenes are a recollection of his past or a fantasy of his future, his experience keeps him outside the society that seeks to destroy him. Eventually the two protagonists get caught by some German-speaking men, who drink and eat noisily to celebrate capturing the boys, before they line up to publicly execute them. It ends without resolution; the boys are both shot and not shot; the film offers both possibilities and no way of answering its uncertainty. It’s a remarkable and grim film. It’s only 64 minutes, and I’m relieved when it’s over.

February 16. Thursday. I’m not in work. I don’t do much today. In the afternoon I go for a walk and bump into the poet John Birtwhistle in Broomhill. He tells me about some good film books he’s seen in one of the charity shops and then we discuss the dilapidated role of ritual in contemporary life, before a hearse drives past us and he remembers he has to go to the dentist. I come home and cook some tomato sauce and make pasta. In the evening I watch To Die For (dir. Gus Van Sant, 1995). I come to this mostly because it’s Joaquin Phoenix’s first role as an adult and don’t have particularly high expectations of it, so I’m pleased to find that it’s morbid and salacious dark comedy organised around incredible performance from Nicole Kidman, perhaps one of her best that I’ve seen. I suppose she was mid-way through her relationship with Tom Cruise at this point, so probably had some good insight into a kind of sociopathic drive towards professional perfection and image management at the expense of any meaningful interpersonal connection. David Thomson, in his extremely horny, almost-slobbering book about how much he wants to have sex with Nicole Kidman, writes that To Die For is a real breakthrough role for Kidman in terms of generating an awareness in audiences and producers and casting agencies that she’s good enough to generate and sustain an entire movie, despite the smallness of its budget and Gus Van Sant’s commitment to some kind of independence of technique and style. Here’s a bit of what Thomson writes, just to give you a flavour of this wildly unhinged book: “it might be easier to focus on the critical intersection in the enjoyment of To Die For: the fertile gap between the dumb cunning of Suzanne Stone and the brilliant innocence of Nicole Kidman. For this is not simply a movie where we enjoy Suzanne’s small-town Machiavellian urges. It is one in which we gain much more from seeing the sophistication of Nicole Kidman being put to these ends. Of course, the two personae fit together as tidily and prettily as … well, as Kidman’s breasts in the violet-coloured underwear she sports in one scene.” You horny old goat, David! So much of Thomson’s style expressed in that faux-modest, do-I-dare ellipsis! I’m just flicking through this book and noticing that I’ve underlined a few more choice comments, one of which I will now share: “She bcomes the face on television, her eyes so wide she could do blow-jobs with them.” Next that I’ve put an exclamation mark, and it looks like I stopped reading Thomson’s book shortly after, though he does admit that he knows some of his remarks are in ‘bad taste’, “but bad taste is exactly what this frigid nation and its anxiety-ridden cinema requires. The great virtue of To Die For is that it comes close enough to let us realise that.” Anyway, David Thomson’s sweaty-palmed ogling aside, To Die For is really excellent. It reminds me of Paul Schrader’s Auto Focus (which of course was made seven years after Van Sant’s film) in its concern with the mismatch between the brightly-coloured cheerfulness of American suburbia, and the sordid eroticism that simmers beneath it. And it would be remiss of me not to say something about Phoenix’s performance, which is the reason for my interest in the first place. In To Die For he shoots Matt Dillon in the head and I feel like a generational transference of sexual fixation takes place in the opposite direction to that bullet’s trajectory. Phoenix in To Die For is inhabiting something of Dillon in Over the Edge: the grubby, unwashed, slack-jawed, idiotic, beautiful, mullet-headed adolescent fuck-up, moving in slow motion, sleep encrusted eyelashes. It’s easy to forget, now that Phoenix is the kind of actor who bulks up or slims down to fit his roles, who looks sometimes bearish and sometimes emaciated — like Christian Bale but brought to tears more quickly — that the original appeal of Phoenix was his smudged and brittle awkward tenderness, the psychological darkness that emerges out of his over-sensitivity, almost a stunned naivety about the world his characters have found themselves in.

February 18. Saturday. I get up late after drinking with Scott last night. I accept that I am going to achieve very little today, so I watch two films, both of which I was commissioned to watch an embarrsing long time ago (June and August respectively) but which, for whatever reason, I have failed to get around to. I see this as putting my affairs fully in order before the ultimate termination of this project. First, in the late morning, I watch Big Hero 6 (dir. Chris Williams & Don Hall, 2014), which was commissioned by Joel. Joel has been a big supporter of the commission function of this film diary, even if he has occasionally used it to get me to watch annoying films which I would prefer not to respond to. He assured me, when he commissioned me to write about Big Hero 6, that there was no irony in this request, but something in my heart had hardened against animated films and I kept putting watching this film off, leaving the email I got from Ko-Fi about it in my inbox as a reminder of my failure. I had in fact already seen Big Hero 6, though I don’t quite know when I watched it. I think it’s very likely that I saw it on a plane either to or from California in either 2015 or 2016, and, as is typically the case with the films I was watching on those semi-regular flights, I suspect I would have wept while watching it, because something about the combination of the high altitude, the drinks trolley, the recycled air, and the implicit suggestion on a long-haul flight that now is the time for a full audit of one’s life, means that I always became extremely mawkish and susceptible to crying at manipulative garbage which I would not usually have bothered to watch. I do not cry while watching Big Hero 6 today, though I do have a few moments of recognition: ah, this is probably where I would have cried, if I was watching it on a plane. It’s as if I can register the emotional manipulation as it’s happening, can feel it acting on my psyche, but because I’m relatively close to the ground, instead of at 40,000 ft, I can observe the assertive emotional shifts of the film with a kind of dispassionate curiosity. I suppose this is what Kant was talking about in the third critique. Do I enjoy Big Hero 6? Not especially. I can see why people might like it. It feels very concerned with exposition, as though, conscious of its audience being primarily made up of children, it feels the need to make sure that it is signposting everything that’s happening: the found family narrative, the thematic role of destructive anger in grief, the need for patience around teenagers who are just trying to figure out the world — all of this is explicit, leaving nothing for the audience to put together themselves. I kind of disconnect about five minutes in when the protagonist says, to his older brother, something along the lines of “yeah, well, our parents died when I was three, remember!?” — this is telling not showing, and while I don’t really care about being prescriptive about so-called writing rules like that, I feel like this film would benefit from treating its viewers less like they’re idiots. But, after all, it is a Marvel film, which is why the villain turns out not to be the tech billionaire, motivated by something as simple as greed, but an adult man in pain because of his bereavement. So there’s a possibility of redemption, or something non-violent. Big Hero 6 would be better if the villain was the billionaire and it ended with his death and all of his assets being taken over by a revolutionary faction and used to fund global anti-imperial struggle. Of course, all films would be better if that’s what they were about, so this isn’t really particular to Big Hero 6.

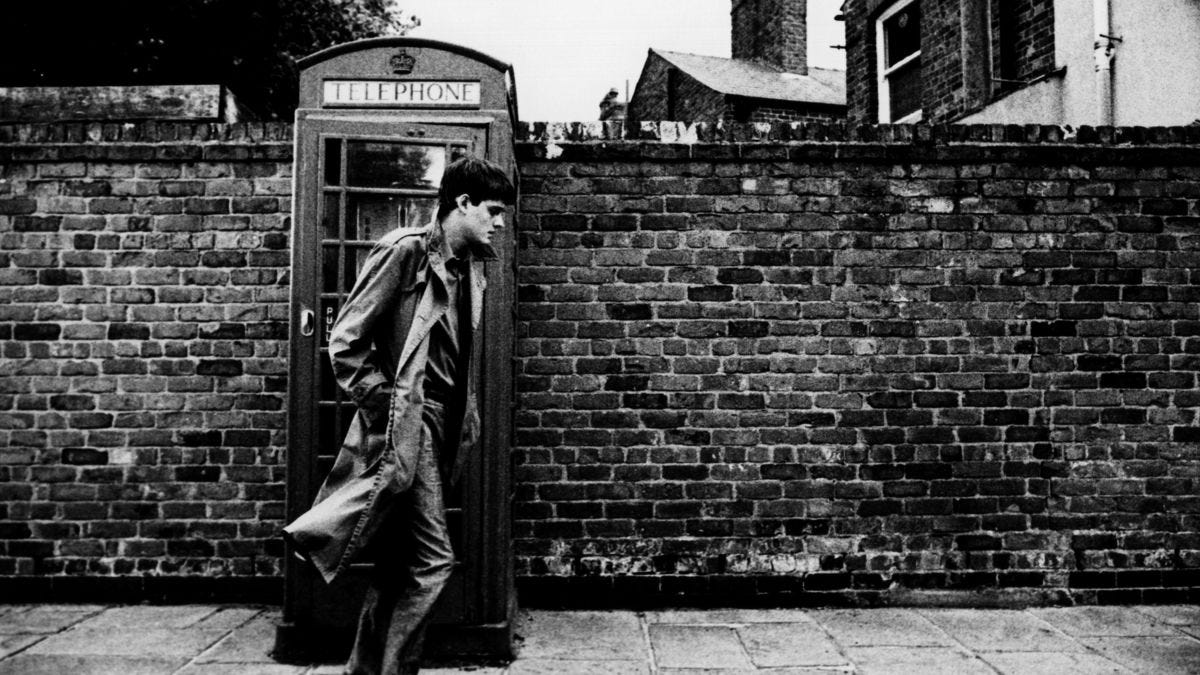

Afterwards, in the mid-afternoon, after a couple of hours of doing nothing, I watch Control (dir. Anton Corbijn, 2007), which was commissioned by Scott. Again, no idea why I put this off for so long. The last time Scott commissioned something for the film diary he got me to watch two massive 1970s period dramas, Cromwell and Waterloo (550 films ago, back in summer 2020, somehow). So perhaps I had created some kind of association in my head between that experience and the idea of watching Control, even though Control is not a historical epic, despite being set in the 1970s. I’ve never really been a huge Joy Division guy, as in, I have certainly heard the music of Joy Division but I don’t think I’ve ever actively and consciously listened to Joy Division, as in, chosen to put on Unknown Pleasures and then paid attention to it, but part of Control’s success is that it reveals to me that perhaps I could become one; that their music is much more than just a way to sell t-shirts to teenagers, or something nostalgic men in their sixties who listen to BBC Radio 6 Music like, which is my more uncharitable, day-to-day habitual way of thinking about them. Anyway, Control is a very very solid musical biopic, with some really excellent performances. Sam Riley is very good. Samantha Morton is, as always, very good. I would watch a film of Samantha Morton taking the bins out, frankly. The real appeal of Control for me, and I think this is why Scott wanted me to watch it, is its depiction of the miserable, grey, squalid, depressing fact of everyday life in the English Midlands — the abyssal greyness of Macclesfield, the tedium of Cheshire, the drab, damp, mouldy buildings, the hacking coughs, the dinginess and parochialism. There’s a good scene in which Ian Curtis comes back from playing a concert somewhere and just looks around his terraced house in silence, and it’s a very clear and immediate depiction of depression: the too-close view of the world and its smallness; the awareness of its wrongness. In so many of the shots, you can see the edge of the Peak District in the background, just behind the town, but it’s the weird bit of the Peak District, just on the far western edge, near the area around Buxton which isn’t part of the national park because it’s been heavily quarried over the years and is no longer the kind of beautiful landscape that national park advocates cared to protect. So Macclesfield in Control has this suggestion of ‘nature’ on the horizon, but nobody ever seems to think to go there, and in fact, the hills start to feel more oppressive than anything else. This might seem incidental, or like an accident of geography, but considering that one of the early scenes in the film involves Ian Curtis reciting a Wordsworth poem from memory (“My Heart Leaps Up”), I don’t think it’s irrelevant. The somehow-inaccessible hills reflect the alienation of the people in the film. I don’t mean to imply that if Ian Curtis had bought some walking boots and starting rambling at the weekends, instead of going to Manchester to play gigs, then he might have been happy. But I think there’s a concern with this film about claustrophobia, smallness, provincialism, and how these feelings are hard to break out of; Curtis doesn’t want to be stuck in Macclesfield, but Debbie loves it there, and he recognises that he’d be lost without her. He’s stuck between his need to leave and his need to stay: a situation that is not exclusive to difficult and erratic artists. Curtis dies by suicide the day before he’s supposed to go to America, the land of vast expanse, of opportunity; you need to hope to go from the English West Midlands to America.

February 19. Sunday. I read in bed with a coffee in the morning. I am putting off writing this diary, having not written any of it yet this week. I spend the afternoon working on it. Or, more accurately, I spend a few hours of the afternoon reading about wine on the internet and listening to Sun Ra and feeling guilty for procrastinating, and then eventually I force myself to push through my blockage. After I finish I do some chores and then walk to Showroom to watch Tange Sazen and the Pot Worth a Million Ryo (dir. Sadao Yamanaka, 1935), which is showing as part of the Japan Foundation’s Touring Film Programme. That programme has been happening for the past couple of weeks but I haven’t gone to anything, and frankly I nearly don’t bother going to see this film, but I talk myself round by reminding myself that it is extremely unlikely that I’ll get another chance to see this in a cinema anytime soon, and I really should put my money where my mouth is about going to see interesting programming when it happens. And I’m very glad I did make the minimal effort to go see this, because it’s great. Sadao Yamanaka was a contemporary of Ozu and Mizoguchi who died in 1938, aged 29, after being drafted into the imperial Japanese Army and catching dysentery in Manchuria. He directed a bunch of films, many of them silent, and it seems like only a couple have survived. I really don’t know much about him other than that potted summary which I gleaned from Wikipedia, and I hadn’t heard of him before I decided to go see this film, but apparently Akira Kurosawa said this film, also known in English as The Million Ryo Pot, was one of his favourite Japanese films ever, and Yamanaka seems to have been a luminary whose death is a loss to the development of global cinema — I suppose like a Japanese Jean Vigo. The Million Ryo Pot is a light, humane comedy about down-and-outs. It revolves around the efforts of a wealthy warlord and his cronies to find an old pot which has a treasure map leading to the location of one million ryo (no idea how much that is but it’s a lot) drawn under its glaze. The warlord has given the pot, which he assumed was worthless, to his brother, who has gotten married and moved out. The brother’s wife doesn’t like the pot and sells it to a junk merchant, who gives it to a child to keep his goldfish in. Everyone starts looking for the pot, but the pot is a McGuffin. At no point does anyone stop to reflect on how exactly they intend to get the glaze off the pot to see the treasure map beneath it, a task which is not really feasible. The reason nobody discusses this is because it doesn’t matter — the pot is just there to give the characters something to look for, while the audience is conscious that it’s beneath their eyes the whole time, and the true value of the pot is the pleasure it gives to the child. There’s a lot more here than the pot and its worth, obviously (it is a nice pot — and along with Ugetsu I would say this is one of the greatest Japanese films in which pottery plays a central role); really this is a quiet, amusing, tender-hearted and fond film about humanity. Yamanaka is fond of one particular joke and repeats it consistently: he gets a character to insist they’re not going to do something and then cuts to a scene in which they’re doing what they said they wouldn’t be doing. This gets an appreciative chuckle from the audience, including myself, every single time. It is really a very lovely, warm film. If you read the reviews on Letterboxd lots of people compare this to Hawks, which makes sense, but Yamanaka seems less concerned with homosociality than Hawks and more open to deflating the pretences of masculinity. Anyway, it’s a treat. If the Japan Foundation touring programme is near you and you get a chance to see this in a cinema I strongly recommend it. You can probably watch it online somewhere too, if you can’t get to it in a cinema.

Dear friends — four films left now. This is surely the penultimate instalment of the film diary. A lot of new readers signed up after the Vittles piece came out; sorry you got here so late. Stick around for the end, or take out a subscription to look through the archives. As always, you can express your gratitude financially. Or you can email me and let me know what you think about whatever it is I’ve been doing here — a few of you have been doing that and I’ve been enjoying it. If I’ve not gotten back to you yet, I will do as soon as I can. Thanks again for being with me here. A