roland barfs film diary week 8: IT IS THE END OF ROLAND BARFS FILM DIARY

three minutes: a lengthening, mandy, a river called titas, putney swope

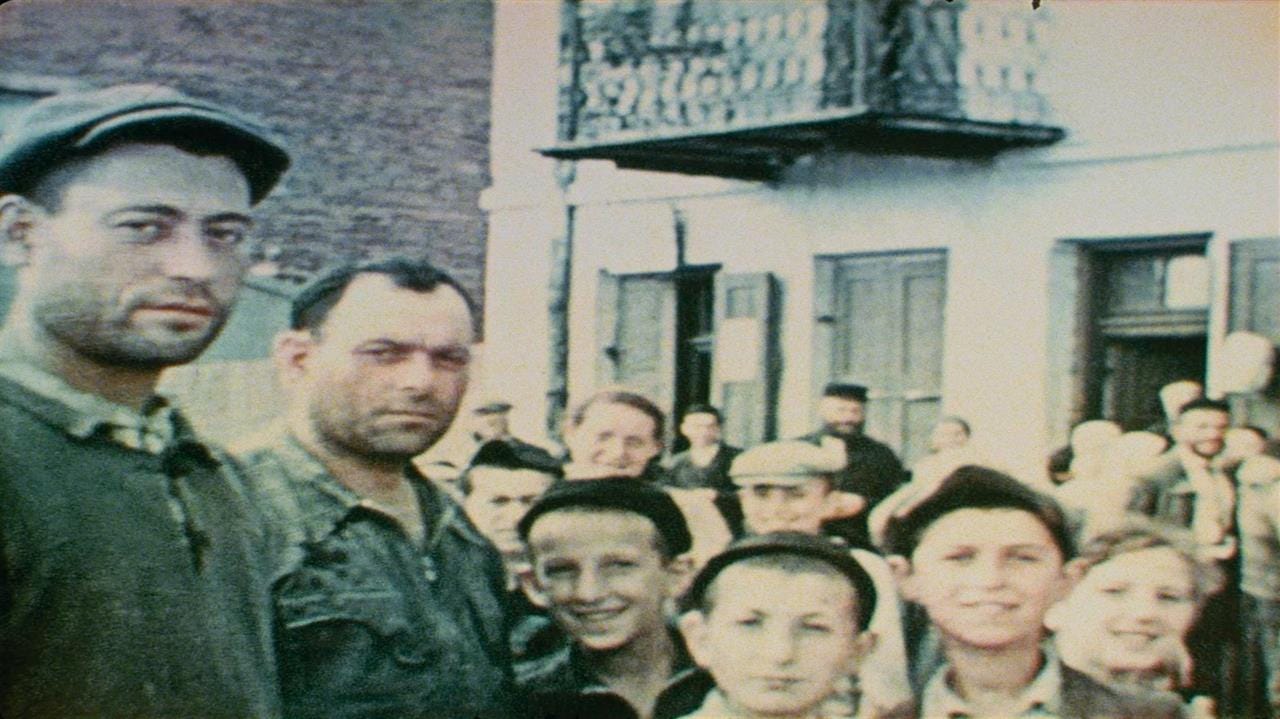

February 20. Monday. I go to Huddersfield for work. I come home. I’m out the house for eleven hours. L is inundated with work, since her strike has been paused (temporarily?), and has spent the day marking. She spends the evening reading George Eliot for a class. I drink two glasses of wine and watch Three Minutes: A Lengthening (dir. Bianca Stigter, 2021), which is currently on BBC iPlayer, as well as a bunch of other streaming platforms. This is a documentary about — what else? — the Holocuast. Specifically, it’s a documentary about three minutes of footage from the small Polish town of Nasielsk, shot in 1938 and then forgotten about for decades, until it was found in a closet in Florida. The film is based on a book by Glenn Kurtz, the guy who found the footage in his grandfather’s closet; Glenn’s grandfather, who was born in Nasielsk, shot the film while on a homecoming trip a year before the Jewish community in the town was deported. I watch this as homework, because I am hoping to arrange something around this film as part of my job, so part of me is a little apprehensive beforehand — what if it’s not very good? Holocaust documentaries are unfortunately a mixed bag, so I am relieved to find that Stigter’s film is thankfully excellent. When the footage was found, it was entirely stripped of context; just three minutes of some faces without names, in a town that has no distinguishing features. There’s a synagogue, there are crowds of people jostling around the camera, there is a feeling of disruption and excitement and novelty, but there’s seemingly no way of identifying anyone who was — more or less accidentally — captured in the foootage. This is not deliberate documentation; it’s an amateur holiday film. The actual film was in such poor quality, almost ruined by vinegar syndrome, decomposing and nearly unwatchable; it was restored by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C. and shared online. Eventually someone happened to watch it who recognised her grandfather in the film, and gradually the people captured by chance can begun to be identified — though not very many of them. It’s a film about close reading, in a way: about a kind of forensic and desperate attempt to decipher information which has nearly disappeared. Some of the most emotionally intense moments in the film for me are those which centre around the efforts to decipher a sign on a greengrocer’s shop in the background; this intensely laborious effort to read a smudge or a blur that is completely opaque, in the hopes that doing so might lead to the identification of the names of a few more people who were murdered by the Nazi regime. Towards the end there is a moment in which still screenshots of every single different face in the film is shown, one after the other, andd then assembled as part of a mosaic — just a snapshot of everyone who was deported from Nasielsk in 1939. It reminds me of the sections at the middle of Daša Drndić’s books, in which she takes pages and pages to list the names of murdered Jews. Except in Stigter’s film, we only have faces, and, thanks to a mixture of obsessive research and commitment, about eleven or twelve names. Really it’s concerned mostly with the fragility of memory, even about something as recent as the Holocaust, how close we are to forgetting, to losing access to any kind of knowledge or awareness — let alone understanding — of these events, which only took place 84 years ago. It’s almost too much to think about: the abyss of oblivion, the ease with which things fall into it and become unrecoverable, how fortunate we are that any trace survives of this encounter with a world which was systematically destroyed by fascism. It is really worth watching. But of course, I would say that, now that I work at a Holocaust archive and museum.

February 21. Tuesday. I go to Huddersfield for work. I come home. I am no longer interested in reflecting on the minutiae of my everyday life. I listen to a podcast on the train home and then remember why I never listen to podcasts. L gets home a little bit after I do and we eat some chips and watch Mandy (dir. Panos Cosmatos, 2018), which was commissioned by LiHe (thank you LiHe). L stops watching after forty-five minutes, saying she’s got the gist. This means that she misses the part of this film where it satisfies the preoccupation with genre set up in the first hour or so, the Nicolas Cage revenge slasher denouement component of the film. I think Mandy is an OK film, but I am conscious through out that it is not really for me. Panos Cosmatos doesn’t care if people like me like this film. It is the work of a genre fanatic, lining up all his favourite Action Men and making them kiss. If you’re into the kitschier, pulpier side of cosmic horror then you’ll like this. If you wish Hellraiser was more in tune with the aesthetics of One Perfect Shot, or if you’d be interested in trying your hand at making something that other people might describe as ’Lynchian’ if they were being generous, or if you wish John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness felt a bit more stoned and was more knowingly referential, then you’ll probably like Mandy. That perhaps sounds like I didn’t like it. I thought it was fine, but I spent most of the film thinking about the ways I might like it better if I either had different tastes or was in a different frame of mind (i.e. stoned). It feels slowed down — I saw someone on Letterboxd describe it as feeling like a 45rpm record played at 33rpm — and ‘dreamy’ in the way that media which has been confected in a basement purely with the intention of satisfying brains with overstimulated cannabinoid receptors might feel ‘dreamy’. This is a stoner film for stoners, and that’s fine, but because I’m not stoned when I watch it, really all I can think about is what it’s like having a conversation with someone who is stoned when you are not stoned, and how that can be kind of annoying, but also kind of sweet and funny and endearing, when they take a long time to say anything and get distracted midway through their thoughts. I did not think Mandy was as good as Pig, which is really the superior Nicolas Cage revenge film. I liked the bit where the cult leader played by Linus Roache (wonderful name) is talking about how great The Carpenters are. I like some of the stupider special effects. I would have liked the horny BDSM fetish bikers to have a slightly larger role and not to have been dispatched so easily by Nicolas Cage. I like it when Nicolas Cage emits his roar of agony midway through putting back a bottle of vodka in his underwear. I think if I had read more Michael Moorcook or had been a teenager in the 1980s I would have found more to like in Mandy. It’s one of those films that feels as though it has been really considered with a very particular audience in mind, who will be excited by the referentiality and the style and by being stoned while they watch it, and if you’re not part of that audience then, well, it doesn’t really need you as a viewer. Which is cool, in a way. I don’t know. Kind of fun, kind of stupid, I was ready for it to be over about half an hour before it was.

February 22. Wednesday. I don’t go to Huddersfield, but instead work at home. I don’t really leave my laptop all day, other than a brief walk around the corner at lunchtime. I don’t drink enough coffee and feel kind of sluggish. Or maybe I’ve been drinking too much coffee this week. Whatever. In the evening I walk to Showroom to see A River Called Titas (dir. Ritwik Ghatak, 1973), which is showing as part of a series of public lectures and screenings about the cinema of 1973. I haven’t been to any of the other events and this is the last one, but it’s nice that they’re showing stuff like this at Showroom. There’s a pretty good turnout, considering it’s a Wednesday evening screening of a fairly obscure Indian-Bangladeshi film. The only other Ghatak film I’ve seen is The Cloud-Capped Star, which I watched thanks to a commission from Kashif a couple of months ago. I liked that a lot. I think I liked it more than A River Called Titas, which I find to be a bit more of a challenge to my patience. I don’t think I am quite capable of giving it the attention it deserves. Probably that’s because I have a bit of a headache and I’m tired, but it’s a long film — two hours forty minutes — and it ambles along without much propulsion. Characters come in and then disappear, time passes, it feels a little as if there’s no invisible hand of the director hovering behind the film keeping things together, moving along nicely. It drifts — I suppose the really tempting metaphor would be to say that it ebbs and flows, much like the river at its centre. A River Called Titas is Ghatak’s penultimate film and was already considered lost within a decade of being made, so it is really great to get to see this in a cinema; it was restored by Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation and had a now out-of-print DVD release, has been shown at occasional festivals or in retrospectives of Ghatak’s work, but there aren’t UK rights available and this screening was apparently negotiated directly with the Ghatak’s estate. So I feel lucky to have had a chance to see it, and I’m glad I made the time to watch it, even if I find myself kind of, well, bored and disengaged for at least part of the film. I’m sure if I’d tried to watch this at home I would have really struggled to focus and probably would have started looking at my phone after an hour. Instead I try to sit with my impatience and boredom and remind myself that, theoretically at least, I am more interested in films which demand something from the viewer than I am in films which hold the viewer’s hand and lead them in a straight line to the conclusion. There are some astonishingly beautiful shots in this film and some fantastic footage of the riverscapes of Bangladesh. Much like The Cloud-Capped Star, it’s a film that is really concerned with the trauma of partition, but A River Called Titas takes a much more ambitious and allegorical approach to this than Ghatak’s earlier work, never explicitly referring to national politics but instead developing its concerns through an intergenerational family epic that is tinged (more than tinged, really) with melodrama. I spend quite a lot of it trying and failing to remember anything about Jean Renoir’s The River, which I watched in October 2020 and which has almost completely disappeared from my memory. But I do remember feeling quite absorbed in that, the easy mastery of Renoir’s humanistic storytelling making it straightforwarrd to slip into the film’s rhythms. Ghatak’s film is not like that: it doesn’t make it easy for the viewer, it isn’t interested in creating a smooth narrative amble along the riverside, but is constantly slipping away from that kind of cohesion, moving back and forward between characters, rupturing the flow of progression and development. If I was feeling glib I could say Ghatak is trying to be the anti-Renoir here, but I’m sure it’s more complicated than that. While I’m watching it I find it hard to find a footing in it, and I’m kind of longing for it to end, but afterwards it starts to feel more compelling, more interesting, more challenging than I had first thought. It would be good to revisit it, but whether I’ll ever actually do that is another question entirely.

February 24. Friday. I spend the day cleaning the flat, mostly. I also spend some time watching a bunch of TikToks in which middle-aged people record themselves with a filter that makes them look like teenagers and then become upset by what they are shown. Contemporary life is full of such experiences. In the afternoon I go to the pottery studio. I throw a few things that I might actually finish, after a few weeks in which I’ve felt incapable of really throwing anything that I’ve liked. I come home and do a bit more cleaning. I listen to Warren Zevon, like I have been every single day of this year so far. In the evening I walk over to Kate and Catherine’s. L comes there from the train back from Lincoln. Kate tells me that the last few months of the film diary have felt like a scream of desperation that is getting louder each week. How nice it is to be understood by one’s friends. We eat some lentils and pasta and then watch Putney Swope (dir. Robert Downey, 1969). This is it, the last film of the film diary. I didn’t want to watch anything particularly valedictory, or anything which would offer any kind of opportunity for reflection on the process of watching and writing about all these films over the past four and a bit years, or whatever exactly it is I’ve been doing here. Putney Swope is a film which I could really have quite contentedly watched at any point since 2019, and is in fact a film which I’ve started watching at least twice before, only to be put off by either low-quality rips or by the fact that I just haven’t had the patience for it. I was very keen to watch it when I was watching all those films from the early 70s, but never managed to get to it. But tonight it seems to be exactly the thing I want to watch, exactly the film that I’ve been wanting to watch for a long time. It is a very eccentric and anarchic comedy that feels both very much of its time and like it’s very difficult to situate clearly in its particular moment: it is hard to imagine how it would have been received in 1969, easy to believe that it might have been too much even then. As we watch it, our running commentary comes back to Mad Men a couple of times: not just in that Putney Swope is clearly an influence on the TV show, but also because it feels at points like Putney Swope could be a kind of shadow Mad Men, the show it could have been, or the unfilmable final series about what happens after Don Draper achieves California enlightenment — maybe his company is taken over by Black radicals. It is a truly oddball comedy suffused with paranoia and tension, a series of deeply weird and often disconnected jokes, repetitions, moments of almost asinine stupidity, silly names (a photographer called “Mark Focus”, which probably isn’t really very funny out of context, but really benefits from being repeated as much as it is in the film), shot through with a cynicism verging on bitterness and hostility. I really enjoy it. I think probably for the first half an hour or so at least, when we’re all laughing at it quite a lot, it’s hard to tell whether we’re laughing at it because it’s funny or we’re laughing at it because everyone else is laughing at it, but that’s why you watch a comedy with your friends instead of sitting in a dark room on your own mirthlessly acknowledging the jokes. The laughter dies down a little after a while and everyone slips into a state of quiet bafflement; it feels less obviously funny and I start reflecting more on how fucking weird it is that this film exists. It is a kind of American surrealism that you don’t really see very often: it’s not zany or light-hearted; it contains a real note of threat and menace — very reminiscent of Buñuel. I’m not sure if I can think of many films like it, but I can now see the influence of it everywhere. It looks cheap, weird, shabby, and it feels very antagonistic and obnoxious. It’s kind of unbearable, in a way, but it’s also maybe a work of genius. Very complicated. It’s only 85 minutes and probably couldn’t sustain itself for a minute longer. Much like this diary, which is now done! Bye!

A postscript: Will and Joel commissioned me to watch The Pacifier (dir. Adam Shankman, 2005) this week, which serves me right for not actually closing the commission function on Ko-Fi. Obviously, they did this solely to wind me up. I will not be watching The Pacifier, which is a comedy starring Vin Diesel. Instead, I’ve asked ChatGPT to write about it in the style of this diary. Here’s what it came up with:

Day 24 of my cinematic journey and I am left with a bitter aftertaste from "The Pacifier" directed by Adam Shankman. This Disney-produced film stars Vin Diesel as a Navy SEAL who is assigned to protect a family in suburban America, including five unruly children.

The film opens with a rather clichéd and uninspired sequence where Diesel's character, Shane Wolfe, fails a mission in which he must retrieve a valuable government asset. This lack of originality sets the tone for the rest of the film, which relies heavily on tired tropes and overused gags.

As the film progresses, Diesel's character is forced to take on the role of a nanny for the children, which leads to a series of predictable mishaps and misunderstandings. The children are portrayed as caricatures of typical American teenagers, with little depth or nuance to their characters.

The film's attempts at humor fall flat, relying on cheap gags and slapstick that feel tired and dated. Even the action scenes, which should be the film's highlight, feel lackluster and unimpressive.

Perhaps the film's biggest flaw is its lack of self-awareness. It takes itself too seriously, which only serves to highlight its shortcomings. Diesel's character is one-dimensional and the story lacks any real depth or meaningful commentary.

In the end, "The Pacifier" is a forgettable film that fails to leave any lasting impression. Its attempts at humor and action fall short, leaving the audience with a feeling of disappointment and dissatisfaction. This film is not worth your time, and I would recommend giving it a hard pass.

Much to think about here, perhaps. It’s easier for me to focus on the things it gets wrong, instead of the things it gets right. Paragraphs, for example — I wouldn’t be caught dead. If you’ll miss Roland Barfs Film Diary, you can always get ChatGPT to do the same thing for you, but much worse.

That’s it — Roland Barfs Film Diary is done. The end. I’ll keep using this Substack in some form, probably, so don’t unsubscribe, unless you want to. I’m working on an essay about this project and my experience of writing it, and I’ll share that soon. Please feel free to get in touch to share your thoughts about what I’ve been doing, if you have any. As usual, if you want to read back through the archive you can sign up to a paid subscription and peruse to your heart’s content. You can also always express your gratitude financially, of course. Thanks again. What a weird few years it’s been. Take care, and look after yourselves. A

Congratulations! I hope there is someone who picks up the depressive film diary baton. It’s compelling. I know that Thomas Bernhard and people like that are very influential but what is it that you dislike about paragraphs? I think you also said the same about not using italics.